Originally posted to http://blogs.msdn.com/b/cdndevs/archive/2016/01/06/submitting-your-first-pull-request.aspx

Over the last few years, we have seen a big shift in the .NET community towards open source. In addition to a huge number of open source community led projects, we have also seen Microsoft move major portions of the .NET framework over to GitHub.

With all these packages out in the wild, the opportunities to contribute are endless. The process however can be a little daunting for first timers, especially if you are not using git in your day-to-day work. In this post I will guide you through the process of submitting your first pull request. I will show examples from my experience contributing to the Humanitarian Toolbox‘s allReady project. As with all things git related, there is more than one way to do everything. This post will outline the workflow I have been using and should serve as a good starting point for most .NET developers who are interested in getting started with open source projects hosted on GitHub.

Installing GitHub for Windows

The first step is to install GitHub for Windows. GitHub’s Windows desktop app is great, but the installer also installs the excellent posh-git command line tools. We will be using a combination of the desktop app and the command line tools.

Forking a Repo

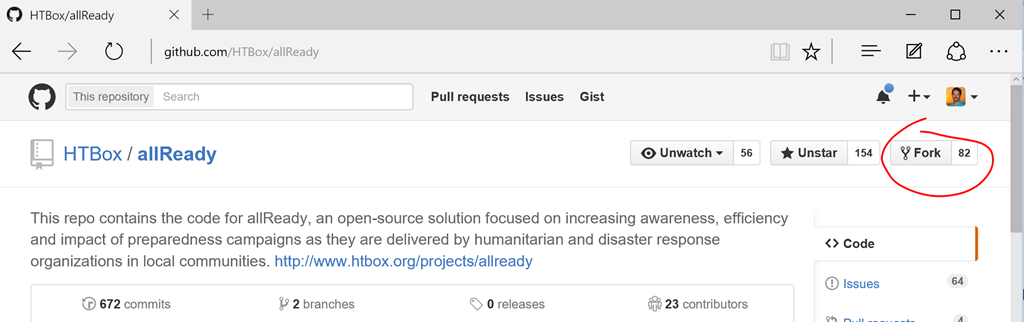

The next step is to fork the repository (repo for short) to which you are hoping to contribute. It is very unlikely that you will have permissions to check in code directly to the actual repo. Those permissions are reserved for project owners. The process instead is to fork the repo. A fork is a copy of the repo that you own and can do whatever you want with. Create a fork by clicking the Fork button on the repo.

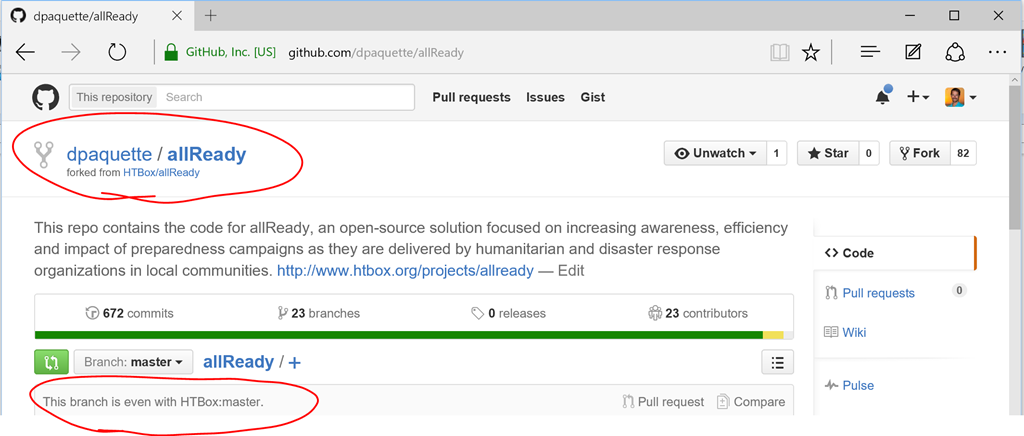

This will create the fork for you. This is where you will be making changes and then submitting a pull request to get your changes merged in to the original repo.

Notice on my fork’s master branch where it says This branch is even with HTBox:master. The branch HTBox:master is the master branch from the original repo and is the upstream for my master branch. When GitHub tells me my branch is even with master that means no changes have happened to HTBox:master and no changes have happened to my master branch. Both branches are identical at this point.

Cloning your fork to your local machine

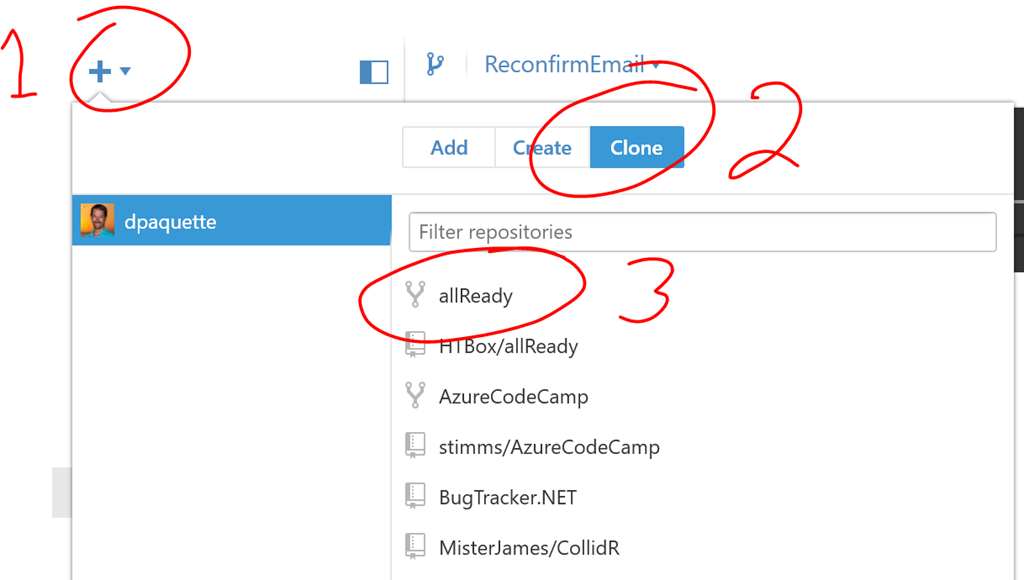

Next up, you will want to clone the repo to your local machine. Launch GitHub for Windows and sign in with your GitHub account if you have not already done so. Click on the + icon in the top right, select Clone and select the repo that you just forked. Click the big checkmark button at the bottom and select a location to clone the repo on your local disk.

Create a local branch to do your work in

You could do all your work in your master branch, but this might be a problem if you intend to submit more than one pull request to the project. You will have trouble working on your second pull request until after your first pull request has been accepted. Instead it is best practice to create a new branch for each pull request you intend to submit.

As a side note, it is also considered best practice to submit pull requests that solve 1 issue at a time. Don’t fix 10 separate issues and submit a single pull request that contains all those fixes. That makes it difficult for the project owners to review your submission.

We could use GitHub for Windows to create the branch, but we’re going to drop down to the command line here instead. Using the command line to do git operations will give you a better appreciation for what is happening.

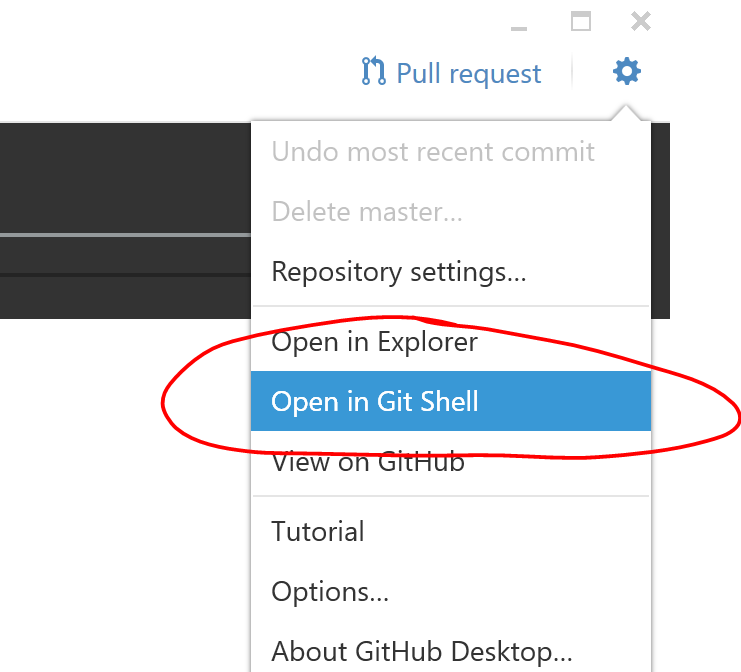

To launch the git command line, select your fork in GitHub for Windows, click on the Settings menu in the top right and select Open in Git Shell.

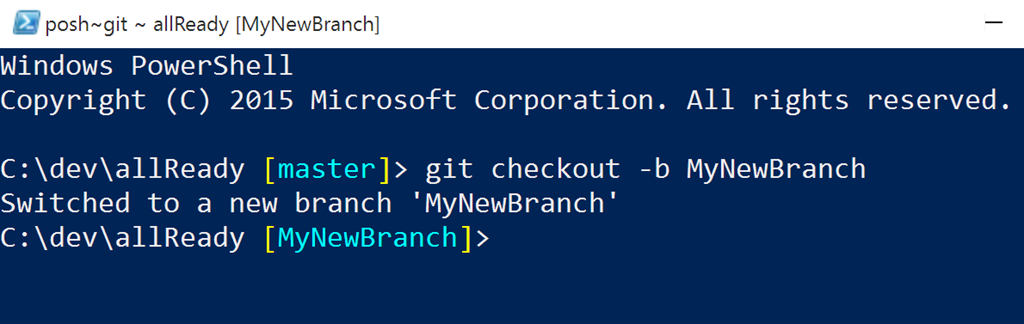

This will open a posh-git shell. From here, type the command git checkout -b MyNewBranch, where MyNewBranch is a descriptive name for your new branch.

This command will create a new branch with the specified name and switch you to that branch. Notice how posh-git gives you a nice indication of what branch you are currently working on.

Advanced Learning: Learn more about git branching with this interactive tutorial http://pcottle.github.io/learnGitBranching/

Pro tip: posh-git has auto complete. Type git ch + tab will autocomplete to git checkout. Press tab multiple times to cycle through available options. This is a great learning tool!

Committing and publishing your changes

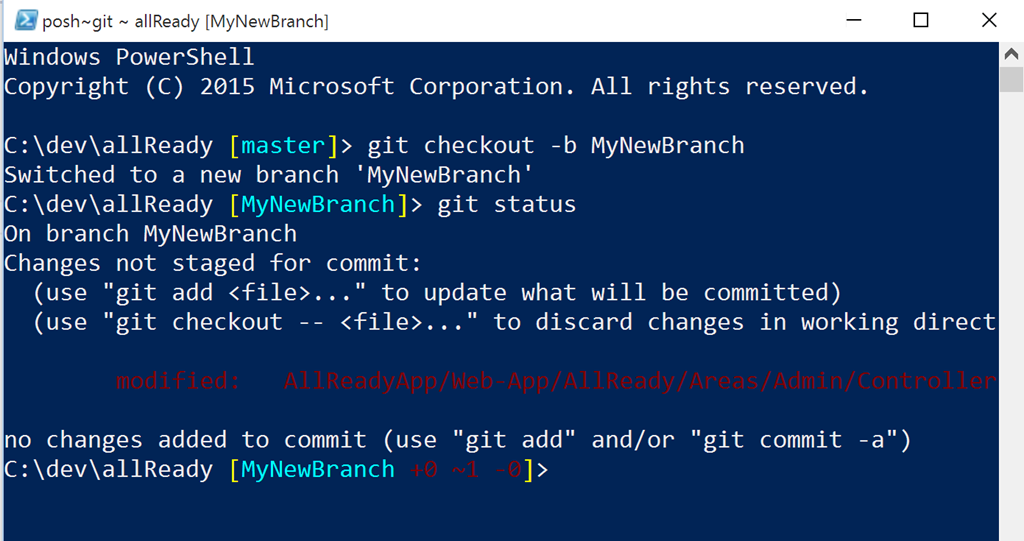

The next step is to commit and publish your changes to GitHub. Make your changes just like you normally would (Enjoy…this is the part where you actually get to write code!). When you are done making your changes, you can view a list of your changes by typing the git status command.

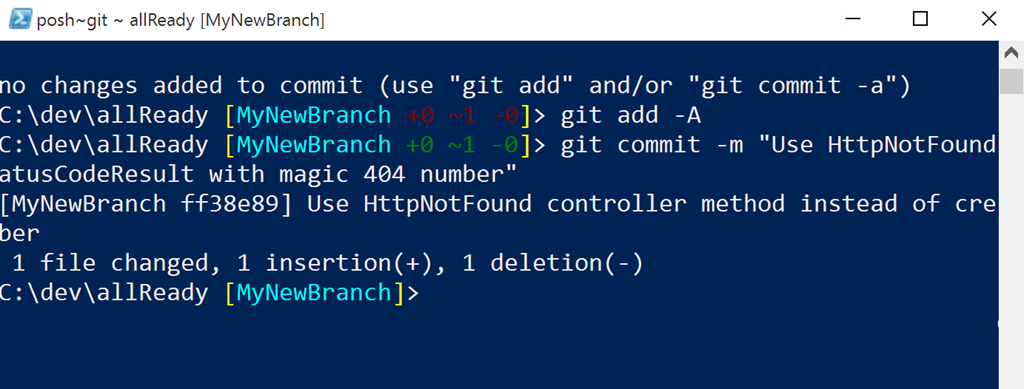

To commit your changes, you first need to add them to your current set of changes. To add all your changes, enter the git add –A command. Note that the git add command doesn’t actually do anything other than get those changes ready to commit. Once your changes have been added, you can commit your changes using the git commit –m "Your commit message" command.

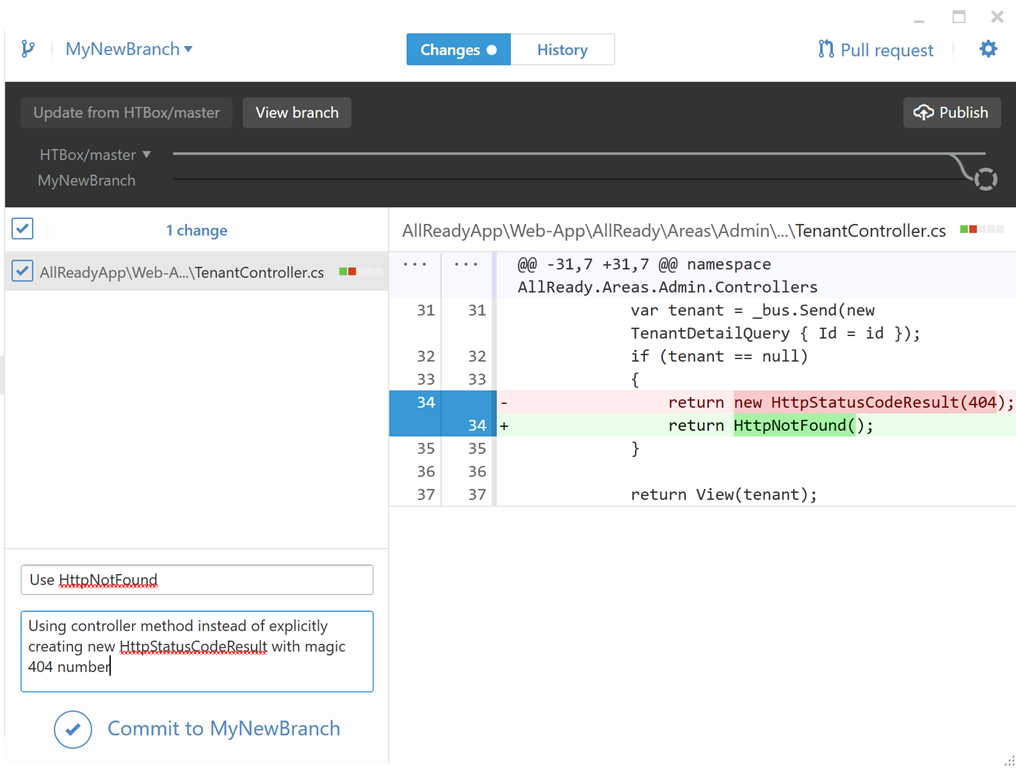

If you wanted to commit only some of the files you changed, you would need to add each of the files individually before doing the commit. This can be a little tedious. In this case, you might want to use the GitHub for Windows app. Simply select the files that you want to include, enter your commit message and click the Commit to YourBranch button. This will do both the add and commit operations as a single operation. The GitHub for Windows app also shows you a diff for each file which makes it a great tool for reviewing your changes.

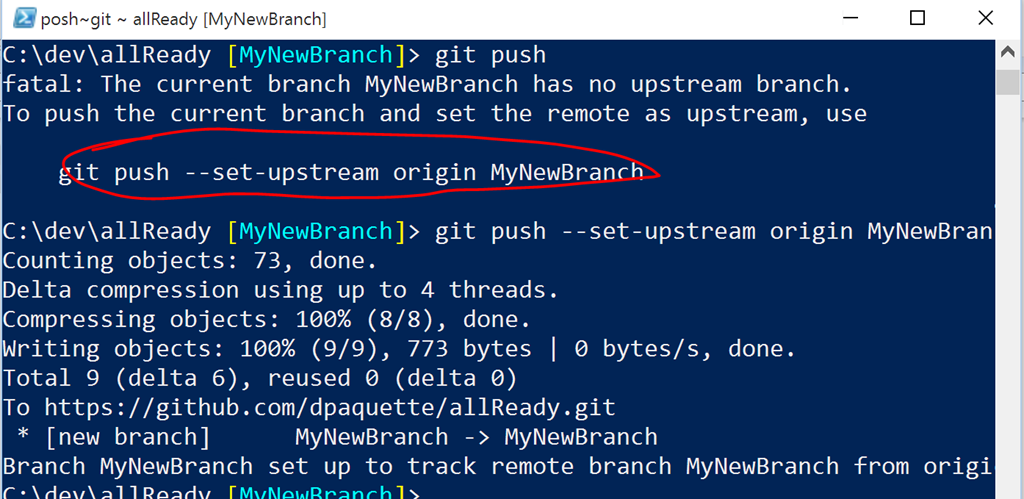

Now your changes have been committed locally, but they have not been published to GitHub yet. To do this, you need to push your branch to a copy on GitHub. You can do this from the command line by using the git push command.

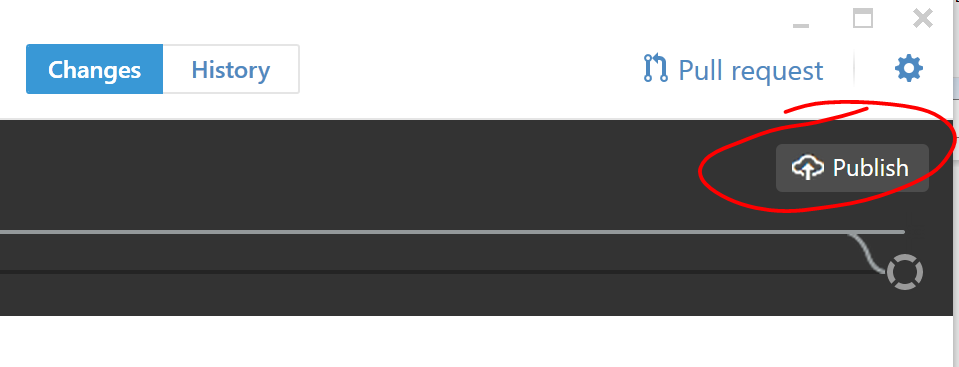

Notice that git detected this branch does not exist on GitHub yet and very kindly tells me the command I need to use to create the upstream branch. Alternatively, you could simply use the Publish button in GitHub for Windows.

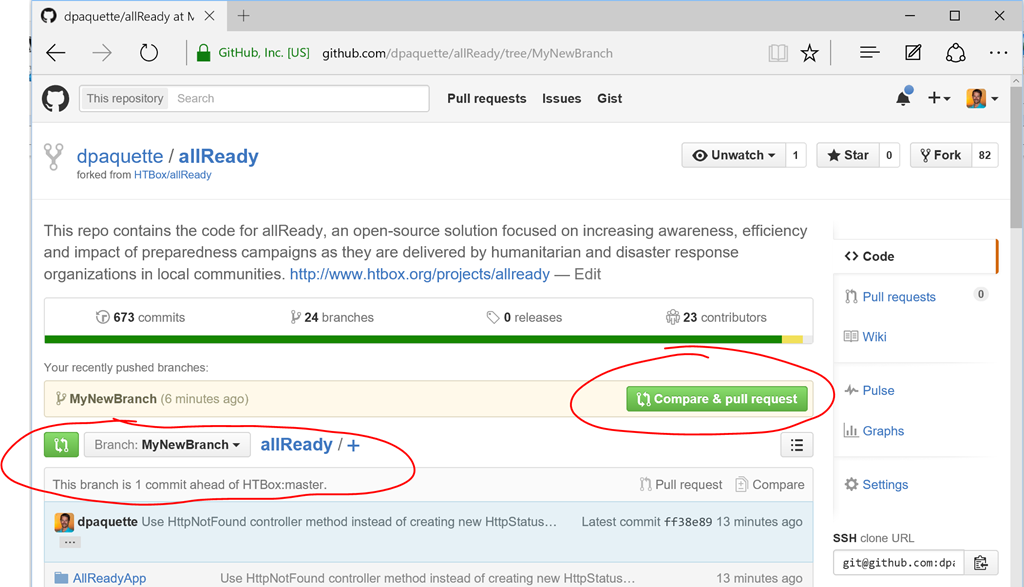

Now the branch containing your changes should show up in your fork on the GitHub website.

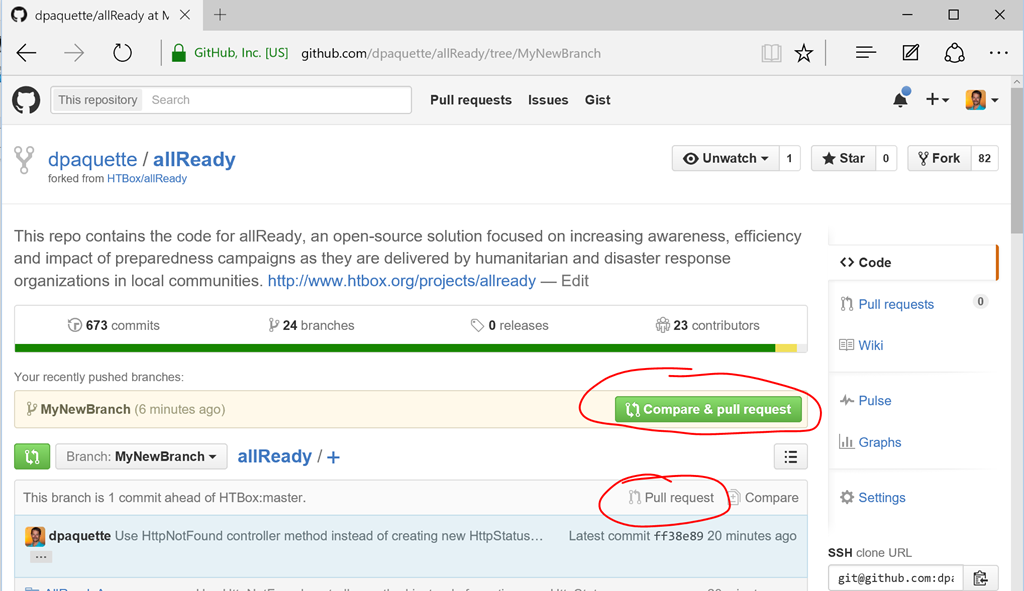

GitHub says my branch is 1 commit ahead of HTBox:master. That’s what I want to see. I made 1 commit in my branch and no one has made any commits to HTBox:master since I created my fork. That should make my pull request clean and easy to merge. In some cases, HTBox:master will have changed since the time you started working on your branch. We’ll take a look at how to handle that situation later. For now let’s proceed with creating this pull request.

Creating your pull request

The next step is to create a pull request so your code can (hopefully) be merged into the original repo.

To create your pull request, click on the Compare & pull request button that is displayed when viewing your branch on the GitHub website. If for some reason that button is not visible, click the Pull Request link on your branch.

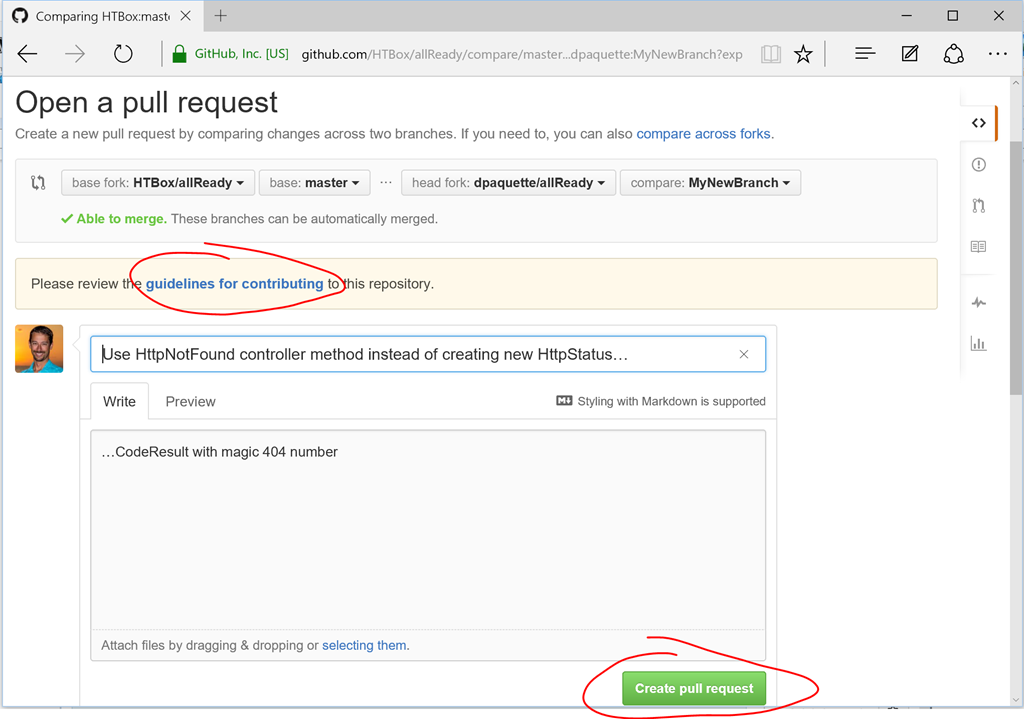

On the Pull Request page, you can scroll down to review the changes you are submitting. For some projects, you will also see a link to guidelines for contributing. Be descriptive in your pull request. Provide information on the change you made so the project owners know exactly what you were trying to accomplish. If there is an issues you are addressing with this pull request you should reference it by number (e.g. #124) in the description of your pull request. If everything looks good, click the Create Pull Request button.

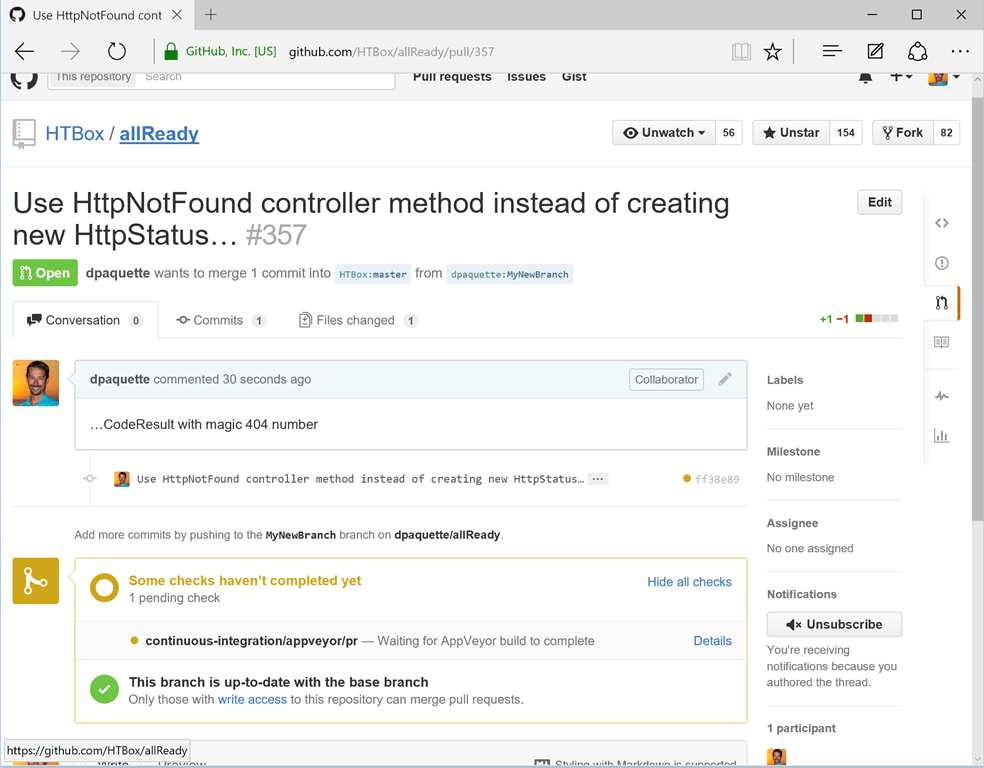

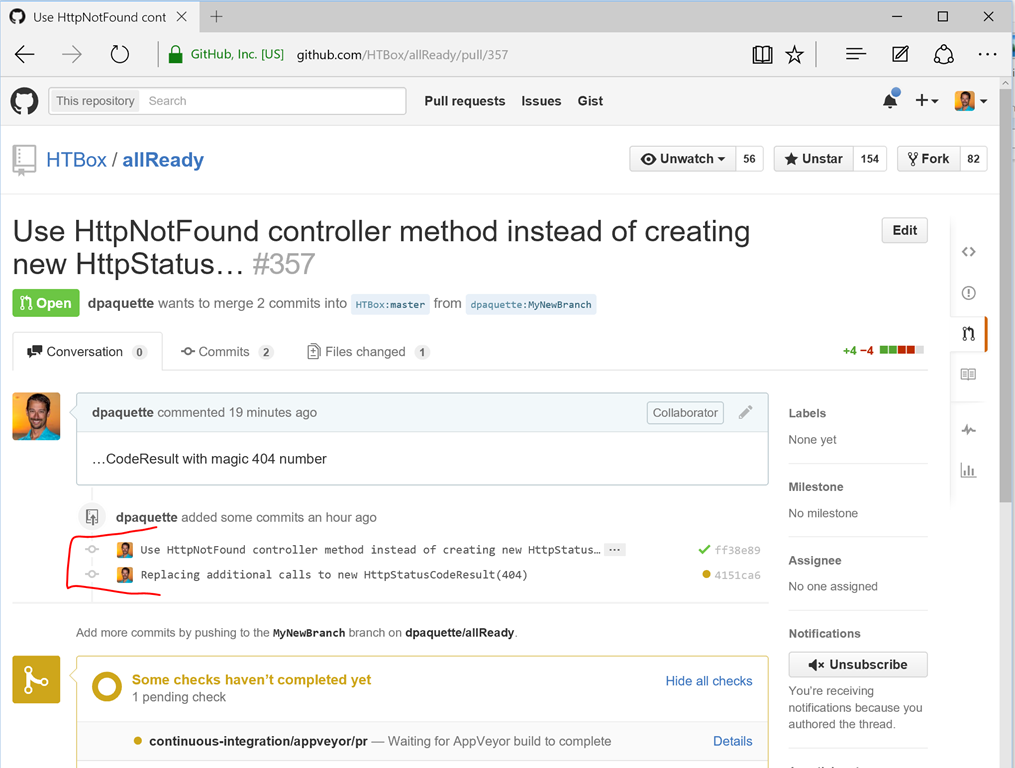

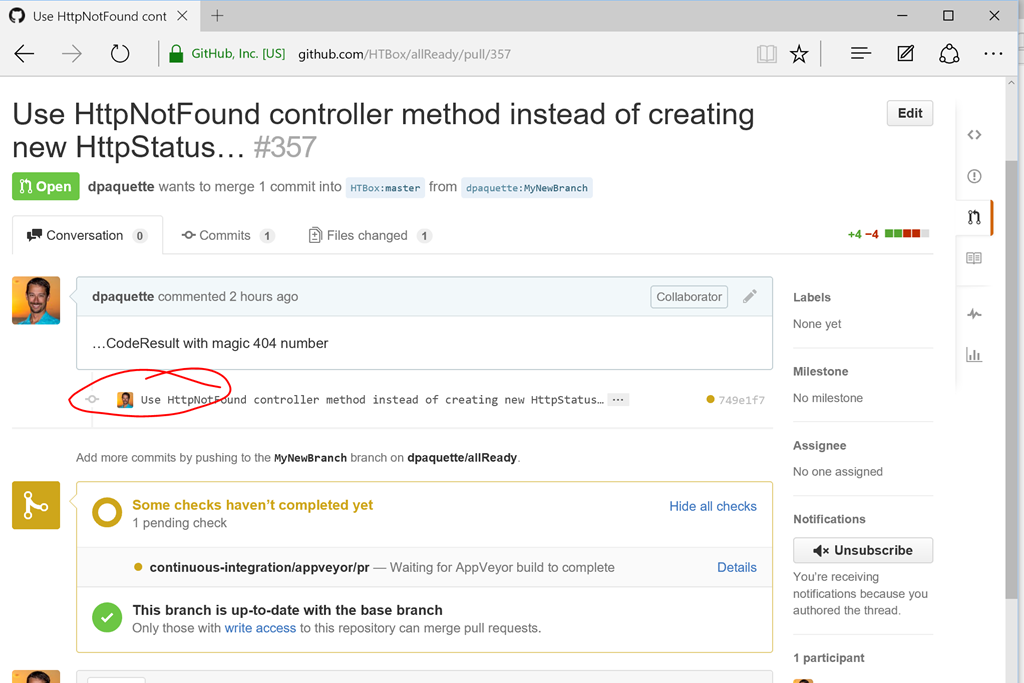

Your pull request has now been created and is ready for the project owners to review (and hopefully accept). Some projects will have automated checks that happen for each pull request. allReady has an AppVeyor build that compiles the application and runs unit tests. You should monitor this and ensure that all the checks pass.

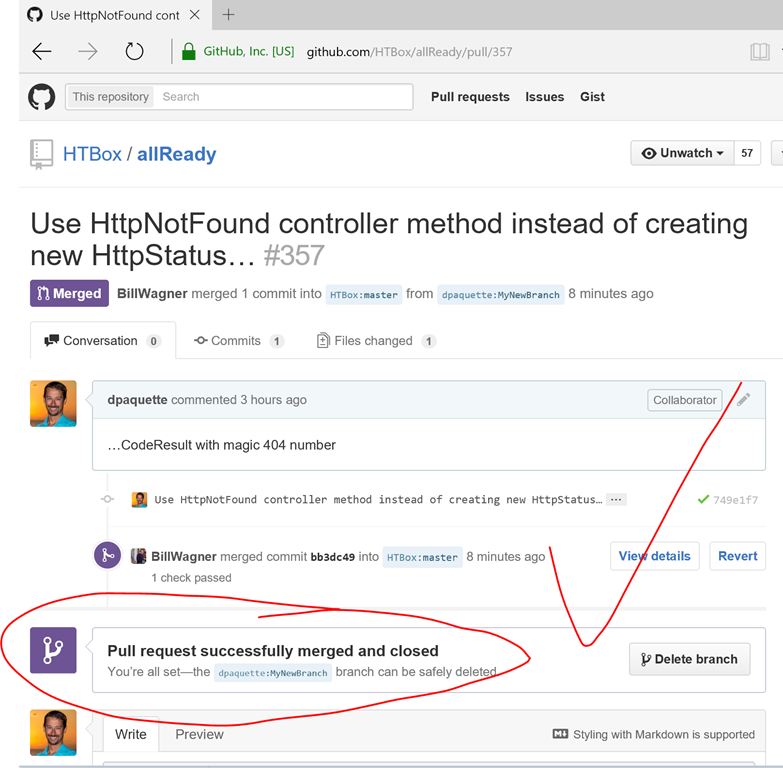

If all goes as planned, your pull request will be accepted and you will feel a great sense of accomplishment. Of course, things don’t always go as planned. Let’s explore how to handle a few common scenarios.

Making changes to an existing pull request

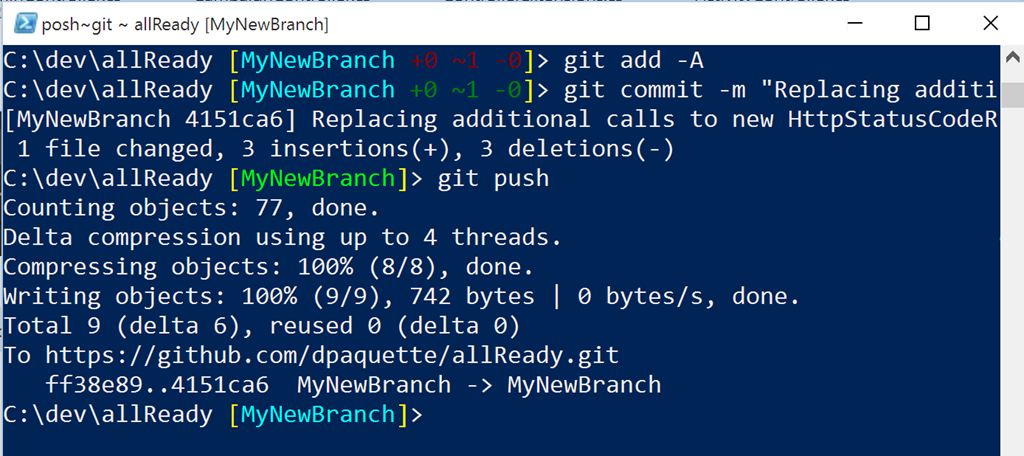

Often, the project owners will make comments on your pull request and ask you to make some changes. Don’t feel bad if this happens…my first pull request to a large project had 59 comments and required a fair bit of rework before it was finally merged in to the master branch. When this happens, don’t close the pull request. Simply make your changes locally, commit them to your local branch, then push those changes to GitHub.

The push can be done using the GitHub for Windows app by clicking the Sync button.

As soon as your changes have been pushed to GitHub the new commit will appear in the pull request. Any required checks will be re-run and the conversation with the project owners can continue. Really that’s what a pull request is: An ongoing conversation about a set of proposed changes to the code base.

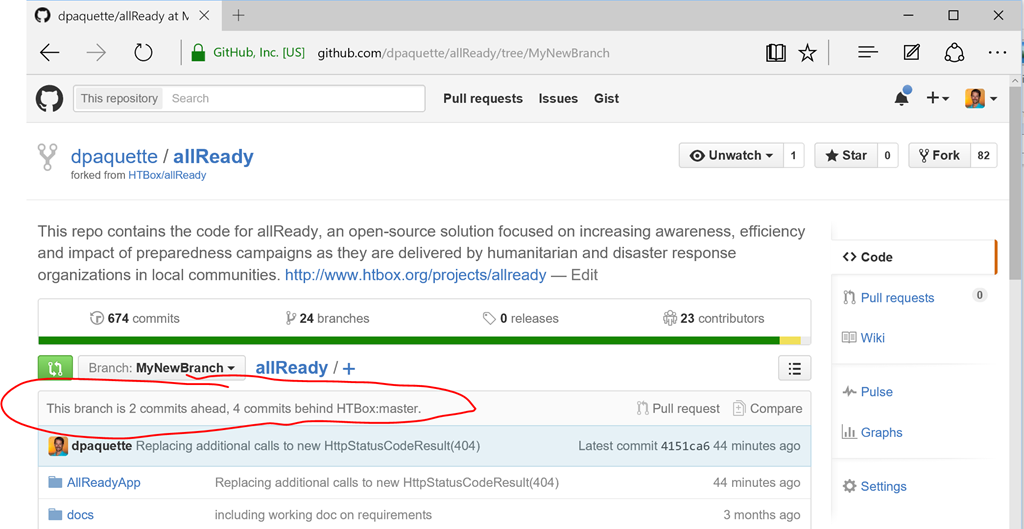

Keeping your fork up to date

Another common scenario is that your fork (and branches) become out of date. This happens any time changes are made to the original repo. You can see in this example that 4 commits have been made to HTBox:master since I created my pull request.

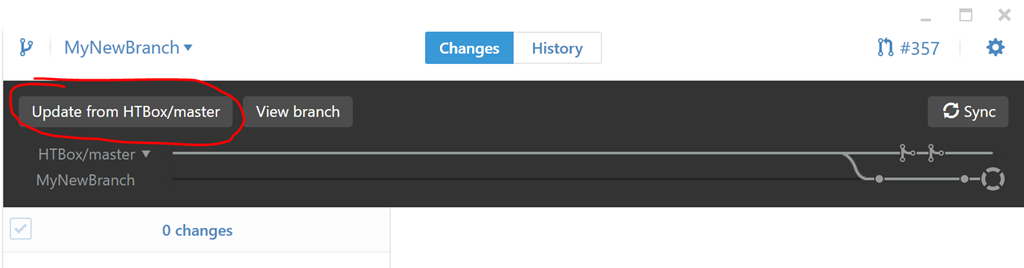

It is a good idea to make sure that your branch is not behind the branch that your pull request will be merged into (in this case HTBox:master). When you branch gets behind, you increase the chances of having merge conflicts in your pull request. Keeping your branch up to date is actually fairly simple but not entirely obvious. A common approach is to click the Update from upstream button in GitHub for Windows. Clicking this button will merge the commits from master into your local branch.

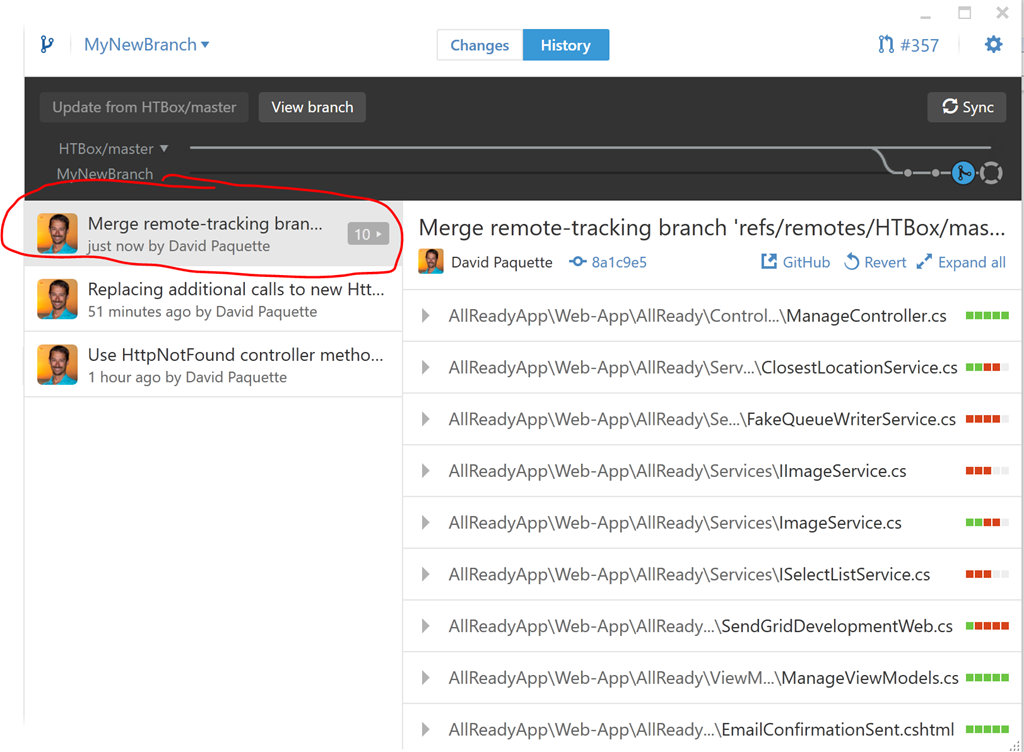

This works, but it’s not a very clean. When using this approach, you get these strange “merge remote tracking branch” commits in your branch. I find this can get confusing and messy pretty quick as these additional commits make it difficult to read through your commit history to understand the changes you made in this branch. It is also strange to see a commit with your name on it that doesn’t actually relate to any real changes you made to the code.

I find a better approach is to do a git rebase. Don’t be scared by the new terminology. A rebase is the process of rewinding the changes you made, updating the branch to include the missing commits from another branch, then replaying your commits after those. In my mind this more logically mirrors what you actually want for your pull request. This should also make your changes much easier to review.

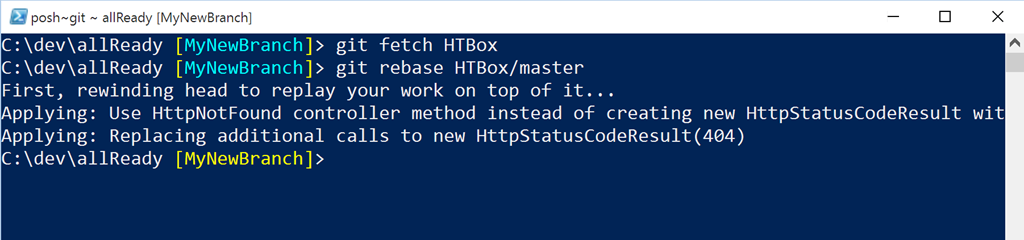

Before you can rebase, you first need to fetch the changes from the upstream (in this case HTBox). Run git fetch HTBox. The fetch itself won’t change your branch. It simply ensures that your local git repo has a copy of the changes from HTBox/master. Next, execute git rebase HTBox/master. This will rewind all your changes and then replay them after the changes that happened to HTBox/master.

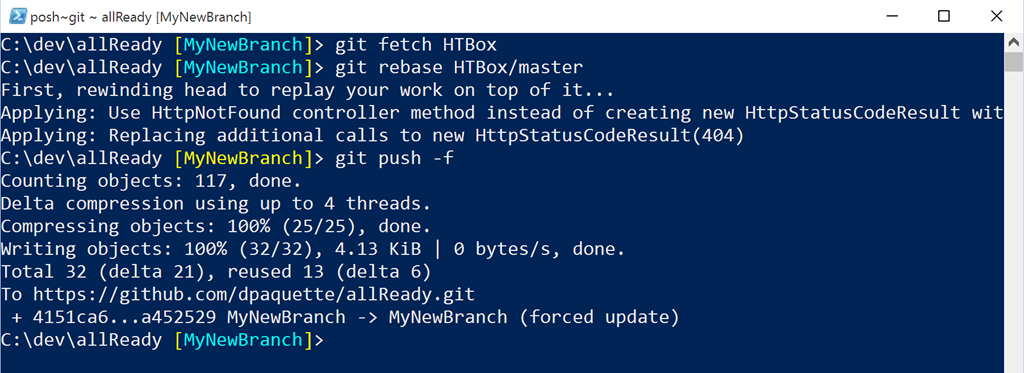

Luckily, we had no merge conflicts to deal with here so we can proceed with pushing our changes up to GitHub with the git push –f command.

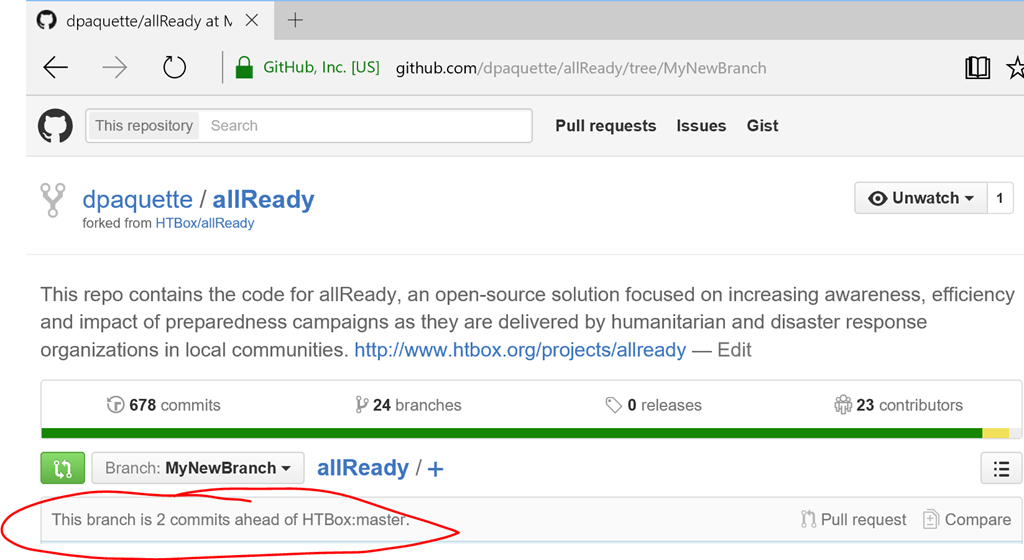

Now when we look at this branch on GitHub, we can see that it is no longer behind the HTBox/master branch.

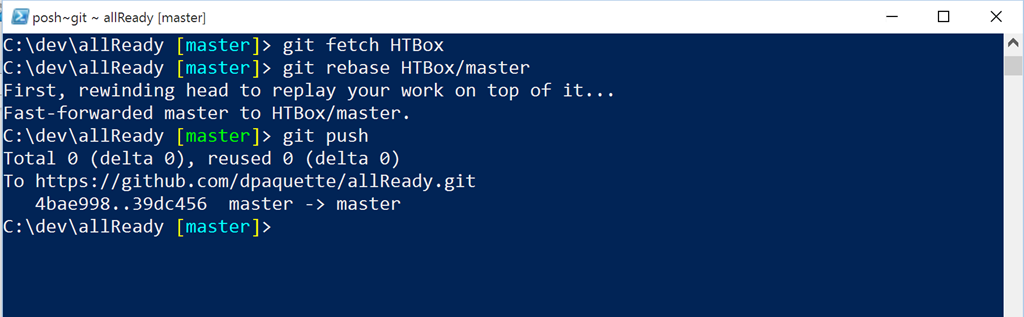

Over time, you will also want to keep your master branch up to date. The process here is the same but you usually don’t need to use the force flag to push. The force flag is only necessary when you have made changes in that branch.

_Caution: _When you rebase, then push –f, you are rewriting the history for your branch. This normally isn’t a problem if you are the only person working on your branch. It can however be a big problem if you are collaborating with another developer on your branch. If you are collaborating with others, the merge approach mentioned earlier (using the Update from button in GitHub for Windows) is a safer option than the rebase option.

Dealing with Merge Conflicts

Dealing with conflicts is the worst part of any source control system, including git. When I run into this problem I use a combination of the command line and the git tooling built-in to Visual Studio. I like to use Visual Studio for this because the visualization used for resolving conflicts is familiar to me.

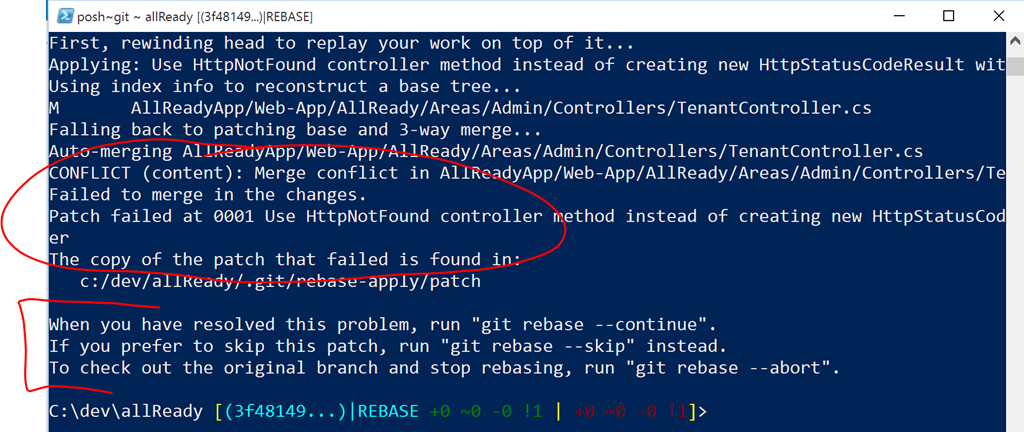

If a merge conflict occurs during a rebase, git will spew out some info for you.

Don’t panic. What happens here is the rebase stops at the commit where the merge conflict happened. It is now up to you to decide how you want to handle this merge conflict. Once you have completed the merge, you can then continue the rebase by running the git rebase –continue command. Alternatively, you can cancel everything by running the git rebase –abort command.

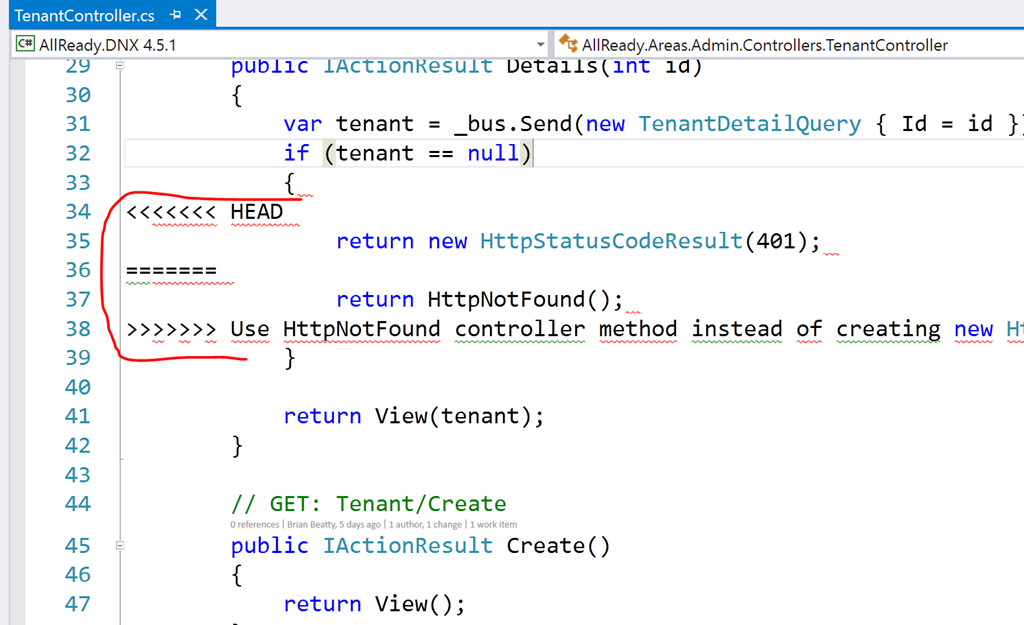

As I said earlier, I like to jump over to Visual Studio to handle the merge conflicts. In Visual Studio, with the solution file for the project open, open the file that has a conflict.

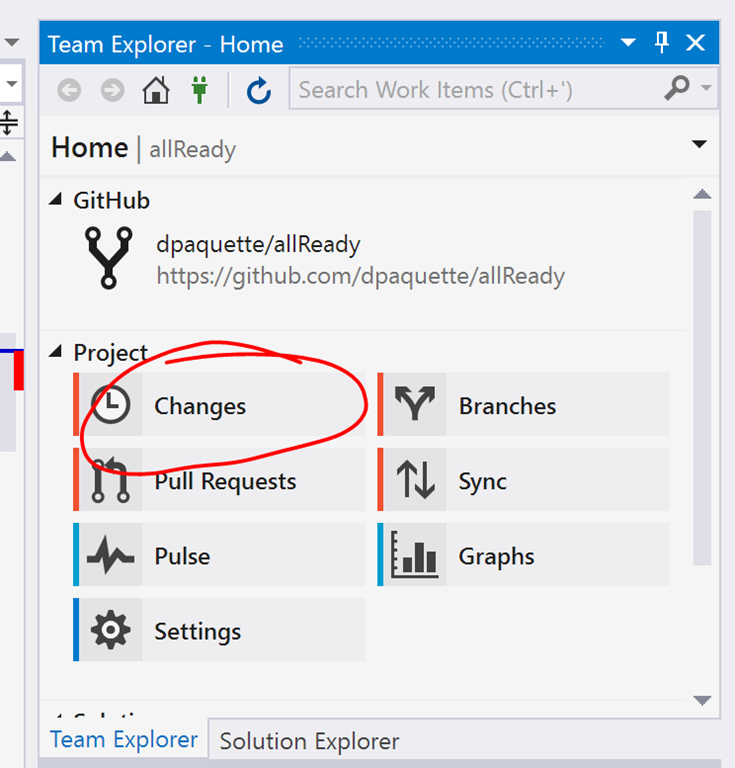

Here, we can see the conflicted area. You could merge it manually here, but there is a much better way. In Visual Studio, open the Team Explorer and select Changes.

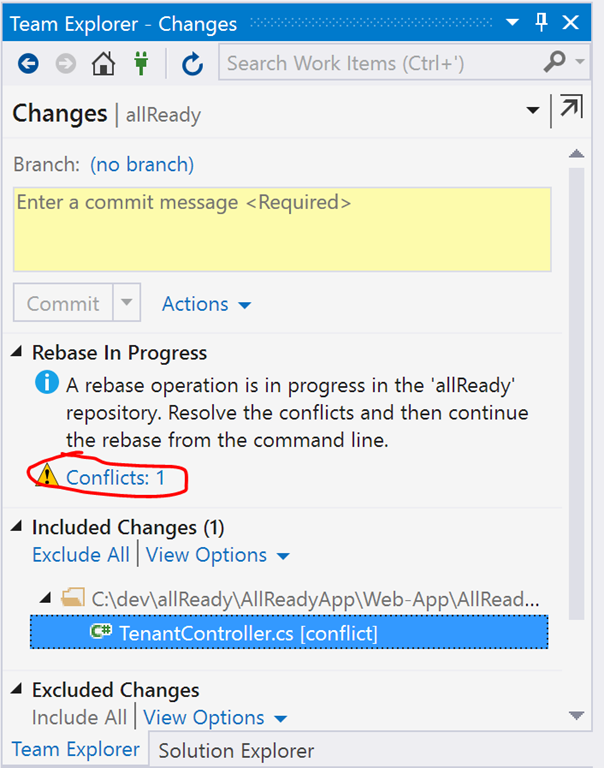

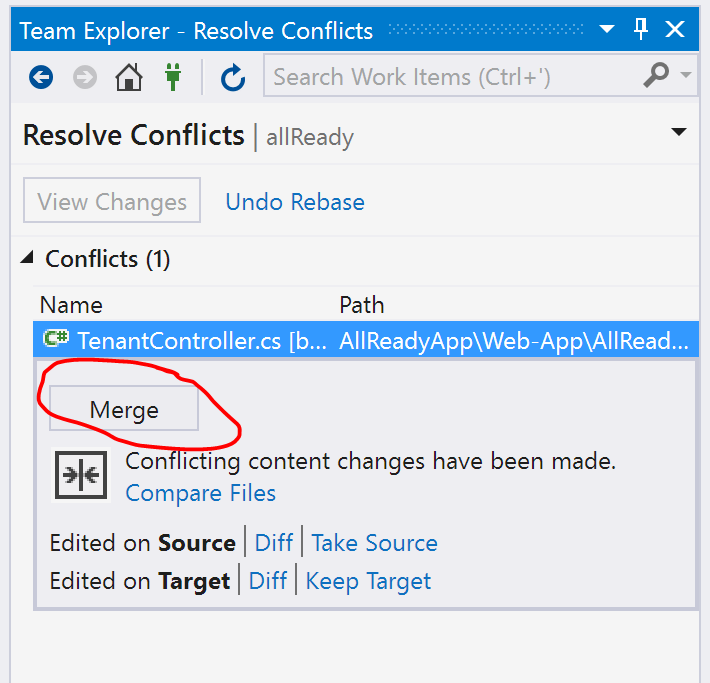

Visual Studio knows that you are in the middle of a rebase and that you have conflicts.

Click the Conflicts warning and then click the Merge button to resolve merge conflicts for the conflicted file.

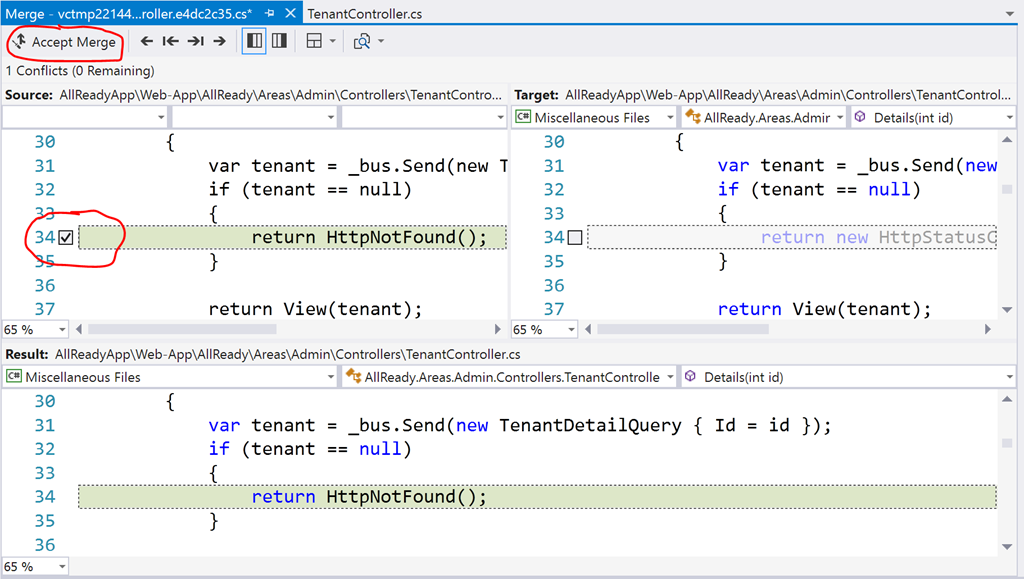

This will open the Merge window where I can select the changes I want to keep and then click the Accept Merge button.

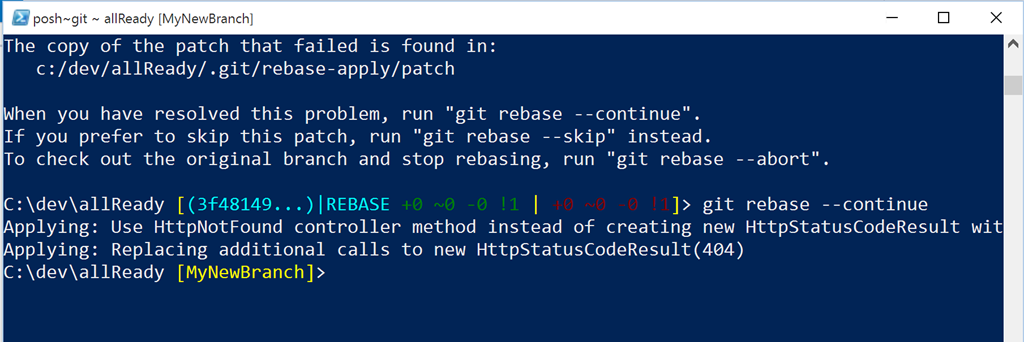

Now, we can continue the rebase operation with git rebase --continue:

Finally, a git push –f to push the changes to GitHub and our merge is complete! See…that wasn’t so bad was it?

Squashing Commits

Some project owners will ask you to squash your commits before they will accept your changes. Squashing is the process of combining all your commits into a single commit. Some project owners like this because it keeps the commit log on the master branch nice and clean with a single commit per pull request. Squashing is the subject of much debate but I won’t get into that here. If you got through the merging you can handle this too.

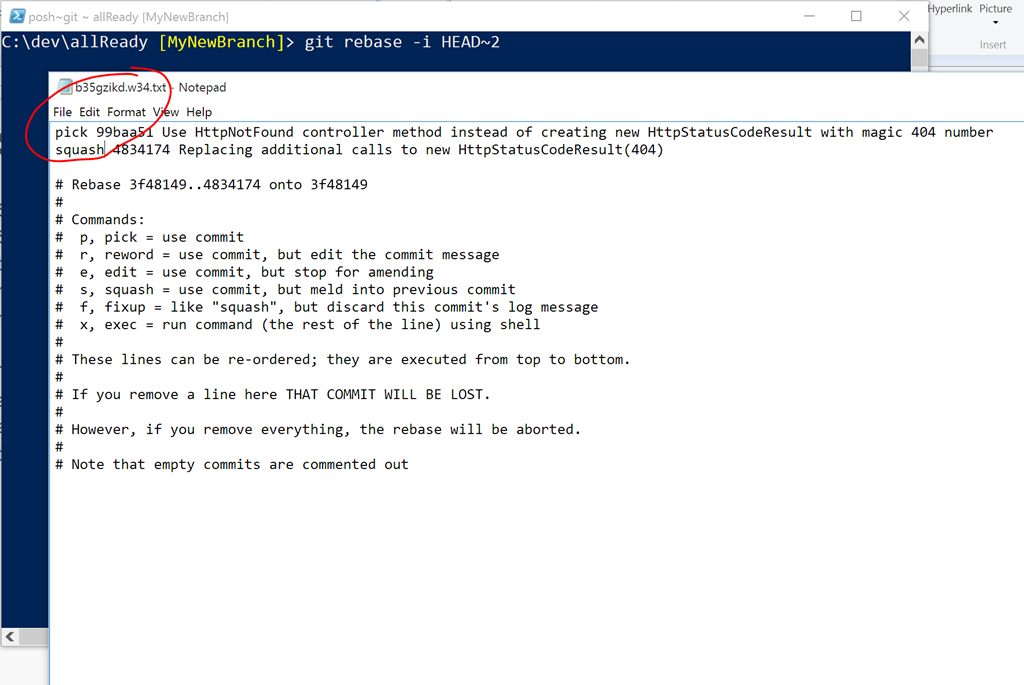

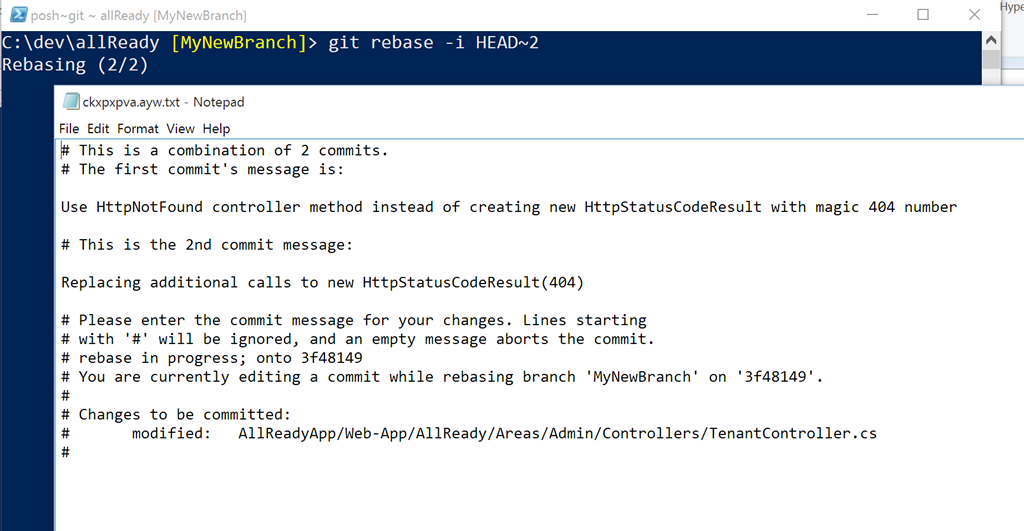

To squash your commits, start by rebasing as described above. Squashing only works if all your commits are replayed AFTER all the changes in the branch that the pull request will be merged into. Next, rebase again with the interactive (-i) flag, specifying the number of changes you will be squashing using HEAD~x. In my case, that is 2 commits. This will open Notepad with a list of the last _x_ commits and some instructions on how to specify the commits you will be squashing.

Edit the file, save it and close it. Git will continue the rebase process and open a second file in Notepad. This file will allow you to modify the commit messages.

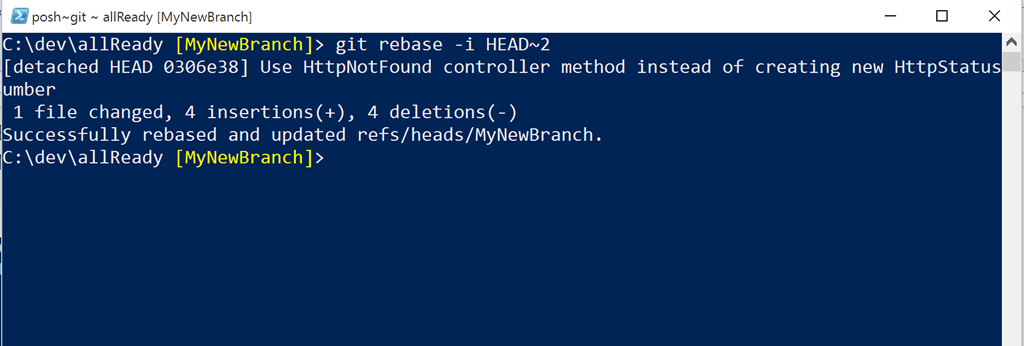

I usually leave this file alone and close it. This completes the squashing.

Finally, run the git push –f command to push these changes to GitHub. Your branch (and associated pull request) should now show a single commit with all your changes.

Pull request successfully merged and closed!

Congrats! You know have the tools you need to handle most scenarios you might encounter when contributing to an open source project on GitHub. It’s time to impress your friends with your new found knowledge of rebasing, merging and squashing! Get out there and start contributing. If you’re looking for a project to get started on, check out the list at http://up-for-grabs.net.